Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Prevention

It is the start of the fall season for our local young athletes and the beginning of the training season for winter sports. With athletics comes the risk of injury, which includes the oft-mentioned Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries. Some of the sports which have been shown to have increased risk for ACL injuries includes men’s and women’s basketball, men’s and women’s soccer, football, and downhill skiing. The majority of these injuries, despite the more well-known traumatic ACL injuries, are non-contact injuries. These non-contact injuries usually include either a planted foot or a twisting mechanism to the knee.

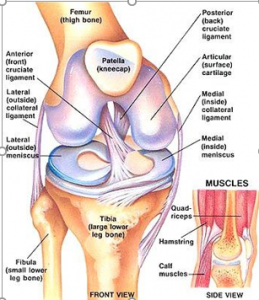

The ACL is one of four major ligaments in the knee and it is in the center of the knee which connects the femur to the tibia. The primary purpose of the ACL is to stabilize the knee by preventing the tibia from moving too far forward (in relation to the femur), preventing too much internal or external rotation, as well as preventing too much extension of the knee. The ACL crosses in front of the not-nearly-as-frequently-injured posterior cruciate ligament forming the cruciates of the knee. Like most ligaments, the ACL does not have a good blood supply and it is not likely to repair themselves following a partial or complete tear.

Due to an increase in awareness of ACL injuries within the athletic population including young athletes, the high profile athletes suffering ACL tears and subsequent repairs, and their lengthy rehab post-surgery, there has been a concerted effort to develop exercise programs aimed at minimizing the risk of these injuries.

The Journal of Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy (JOSPT) has recently published a clinical practice guideline updating suggestions for an effective ACL injury prevention program. This practice guideline outlines a list of suggested components, duration, and groups who would most benefit from this type of program.

JOSPT recommends that exercises focus on a combination generalized strengthening of the legs, plyometric training, proximal control (“core”) training, and stretching of the: quadriceps, hamstrings, hip adductors (groin), hip flexors, and calves. The authors also found that balance training, while important, should not be the sole focus of these programs. The article also suggests that training be implemented multiple times a week with each session lasting at least 20 minutes for a cumulative amount per week greater than 30 minutes. It is also important to maintain compliance with these programs both in the pre-season as well as through the regular season. These programs were found to be particularly important for females below the age of 18 as females do tend to have a higher incidence rate of ACL injuries.

There have been recent studies which show there are a subset of people who have sustained full thickness ACL tears that are able to return to sport without undergoing ACL reconstruction but it is important to discuss your options with your doctor. If you are looking to rehabilitate after an ACL reconstruction, receive therapy prior to getting surgery, or attempting to avoid surgery, the professionals at Spine and Sports PT are well equipped to give you individualized treatment to get you moving and feeling better!

Keith Sayball, PT, DPT, CDN

Our

Our